Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

➜ CHUR 4/151/3-4, 7, 10, 12, 13

I described the course of events at Dunkirk then said quite casually, ‘Of course, whatever happens at Dunkirk, we shall fight on.’ Quite a number of the politicians and MPs seemed to jump up from the table and come running to my chair, shouting and patting me on the back.

Early the next morning, May 27, emergency measures were taken to find small craft ‘for a special requirement’. This was no less than the full evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force. It was plain that large numbers of such craft would be required for work on the beaches, in addition to whatever bigger ships which could load in Dunkirk harbour. Lifeboats from liners in the London docks, tugs from the Thames, yachts, fishing craft, lighters, barges and pleasure-boats—anything that could be of use along the beaches, were called into service. By the night of the 27th a great tide of small vessels began to flow towards the sea, first to our Channel ports, and thence to the beaches of Dunkirk and the beloved Army.

There was never any question of our leaving the French behind. Here was my intial order before any request or complaint from the French was received:

Prime Minister to Secretary of State for War, C.I.G.S., and General Ismay, 29.5.40

It is essential that French should share in such evacuations from Dunkirk as may be possible. Nor must they be dependent only upon their own shipping resources.

The miracle of Dunkirk was in full swing. Various members of the French Government gathered round the conference table. When I told them that over 300,000 men had been taken off they were astonished. When I told them that among these were 120,000 Frenchmen, they were deeply moved.The final phase was carried through with much skill and precision. We had been prepared to carry considerably greater numbers of French that night than had offered themselves. The result was that when our ships, most of them still empty, had to withdraw at dawn, thirty thousand French troops, many still in contact with the enemy, remained ashore. One more effort had to be made. Despite the exhaustion of ships’ companies, the call was answered. On June 4 26,175 Frenchmen were landed in England, over 21,000 of them in British ships.

Finally at 2.23 pm on that day the Admiralty in agreement with the French announced that ‘Operation Dynamo’ was now completed.

TABLE

BRITISH AND ALLIED TROOPS LANDED IN ENGLAND

| Date | From the beaches | From Dunkirk harbour | Total | Accumulated total |

| May 27 | Nil | 7,669 | 7,669 | 7,669 |

| 28 | 5,930 | 11,874 | 17,804 | 25,473 |

| 29 | 13,752 | 33,558 | 47,310 | 72,783 |

| 30 | 29,512 | 24,311 | 53,823 | 126,606 |

| 31 | 22,942 | 45,072 | 68,014 | 194,620 |

| June 1 | 17,348 | 47,081 | 64,429 | 259,049 |

| 2 | 6,695 | 19,561 | 26,256 | 285,305 |

| 3 | 1,870 | 24,876 | 26,746 | 312,051 |

| 4 | 622 | 25,553 | 26,175 | 338,226 |

| Grand total | 98,780 | 239,446 | 338,226 | 338,226 |

…Then I said quite casually, and not treating it as a point of special significance:

"Of course, whatever happens at Dunkirk, we shall fight on.”

Then occurred a demonstration which, considering the character of gathering—twenty-five experienced politicians and Parliament men, who represented all the different points of view, whether right or wrong before the war—surprised me. Quite a number seemed to jump up from the table and come running to my chair, shouting and patting me on the back.

…

Early the next morning, May 27, emergency measures were taken to find small craft "for a special requirement". This was no less than the full evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force. It was plain that large numbers of such craft would be required for work on the beaches, in addition to whatever bigger ships which could load in Dunkirk harbour. On the suggestion of Mr. H. C Riggs, of the Ministry of Shipping, the various boatyards, from Teddington to Brightlingsea, were searched by Admiralty officers, and yielded upwards of forty serviceable motor-boats or launches which were assembled at Sheerness on the following day. At the same time lifeboats from liners in the London docks, tugs from the Thames, yachts, fishing craft, lighters, barges and pleasure-boats—anything that could be of use along the beaches, were called into service. By the night of the 27th a great tide of small vessels began to flow towards the sea, first to our Channel ports, and thence to the beaches of Dunkirk and the beloved Army.

…

There was never any question of our leaving the French behind. Here was my order before any request or complaint from the French was received:

Prime Minister to Secretary of State for War, C.I.G.S., and General Ismay, 29.V.40

(Original to C.I.G.S.)

It is essential that French should share in such evacuations from Dunkirk as may be possible. Nor must they be dependent only upon their own shipping resources.

…

The miracle of Dunkirk was in full swing. Various members of the French Government gathered round the conference table. They had no more idea of what was happening in the North than we had about the main French front. When I told them that over 300,000 men had been taken off they were astonished. When I told them that among these were 120,000 Frenchmen, they were deeply moved….

…

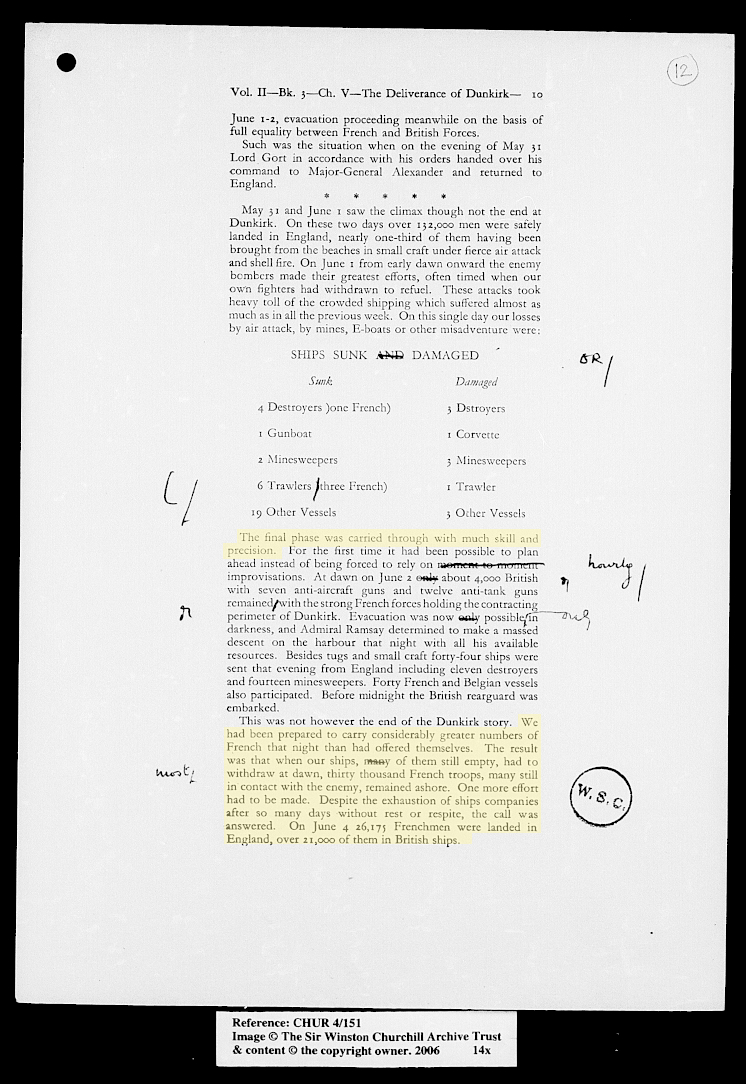

The final phase was carried through with much skill and precision…. We had been prepared to carry considerably greater numbers of French that night than had offered themselves. The result was that when our ships, most of them still empty, had to withdraw at dawn, thirty thousand French troops, many still in contact with the enemy, remained ashore. One more effort had to be made. Despite the exhaustion of ships companies after so many days without rest or respite, the call was answered. On June 4 26,175 Frenchmen were landed in England, over 21,000 of them in British ships.

Finally at 2.23 p.m. on that day the Admiralty in agreement with the French announced that ‘Operation Dynamo’ was now completed.

TABLE

BRITISH AND ALLIED TROOPS LANDED IN ENGLAND

| Date | From the beaches | From Dunkirk harbour | Total | Accumulated total |

| May 27 | Nil | 7,669 | 7,669 | 7,669 |

| 28 | 5,930 | 11,874 | 17,804 | 25,473 |

| 29 | 13,752 | 33,558 | 47,310 | 72,783 |

| 30 | 29,512 | 24,311 | 53,823 | 126,606 |

| 31 | 22,942 | 45,072 | 68,014 | 194,620 |

| June 1 | 17,348 | 47,081 | 64,429 | 259,049 |

| 2 | 6,695 | 19,561 | 26,256 | 285,305 |

| 3 | 1,870 | 24,876 | 26,746 | 312,051 |

| 4 | 622 | 25,553 | 26,175 | 338,226 |

| Grand total | 98,780 | 239,446 | 338,226 | 338,226 |

This is a collection of extracts from drafts of Churchill’s historical account of the Second World War.

Churchill wrote the book, with a team of assistants, using both his own notes and his own copies of official documents from the time. Churchill, because of his status as wartime leader, was given special privileges by the government to publish the official documents he had written during the war (long before others were allowed to). This is one of the reasons why Churchill’s own account of the second world war was very influential. The second volume, from which this extract is taken, was published in 1949, but this is a draft which was written between January 1947 and October 1948. In this chapter, Churchill discusses the use of small craft during the evacuation at Dunkirk and the rescue of both French and British troops. He based his account of the evacuation of Dunkirk on an internal Admiralty narrative from 1948.

Remember we are hoping that this source can be useful to us in investigating whether the Dunkirk evacuation was a triumph or a disaster. Sources usually help historians in two ways:

Which of the inferences below can be made from this source?

| On a scale of 1-5 how far do you agree that this source supports this inference? | Which extract(s) from the source support your argument? | |

| Churchill was pessimistic about evacuating the troops from Dunkirk. | ||

| Churchill wants to be given all the credit for the Dunkirk evacuation. | ||

| It’s likely that Churchill received criticism about leaving the French behind. | ||

| The French were grateful for the British efforts at Dunkirk. | ||

| The Dunkirk evacuation was a triumph. |

➜ Download table (PDF)

➜ Download table (Word document)